Aguacatillo

Persea caerulea

Native Region

Central America and northern South America

Max Height

15-30 meters (50-100 feet)

Family

Lauraceae

Conservation

LC

Uses

Season

Flowering

Jan-Mar

Fruiting

Mar-Jun

Safety Information

Toxicity Details

Aguacatillo is a member of the Lauraceae (avocado family) and contains persin, the same compound found in cultivated avocados. The fruit is small and mostly consumed by wildlife (especially quetzals). While not typically eaten by humans (too small, mostly pit), it poses minimal risk to people. However, like all avocado relatives, it contains persin which is TOXIC TO PETS (dogs, cats, birds, horses) and can cause vomiting, diarrhea, heart damage, and respiratory distress in animals.

Skin Contact Risks

No skin irritation. Safe to handle leaves, bark, and fruit.

Allergenic Properties

Some individuals may have mild allergic reactions to Lauraceae family members, but this is uncommon.

Wildlife & Pet Risks

TOXIC TO PETS - particularly dogs, cats, birds, and horses due to persin content. Can cause vomiting, diarrhea, respiratory distress, and heart problems in domestic animals. Keep pets away from fallen fruit. Ironically, wild birds including quetzals have evolved to safely consume these fruits, making this tree critical wildlife habitat while being dangerous to domestic animals.

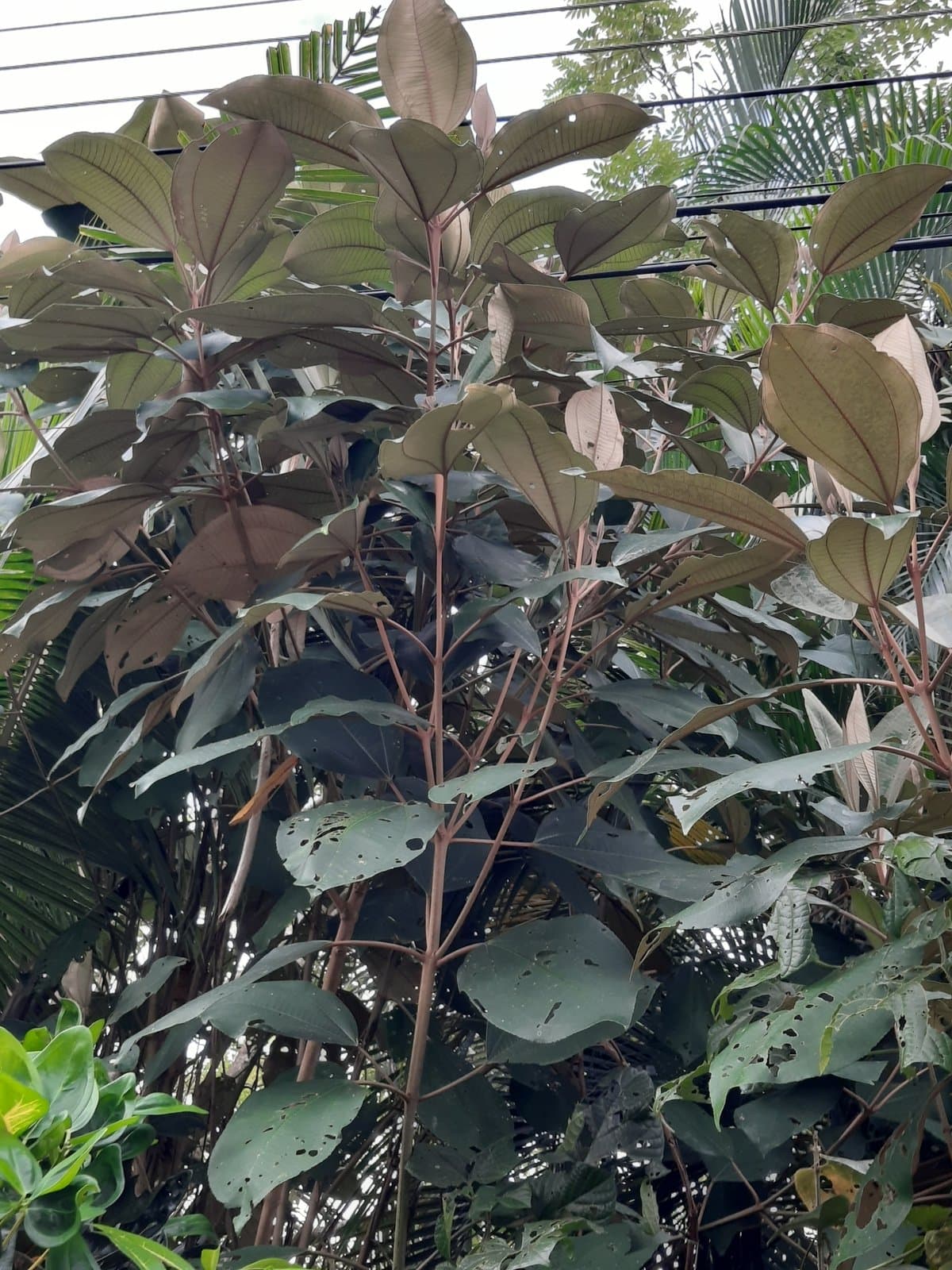

Aguacatillo (Wild Avocado)

The Aguacatillo (Persea caerulea) is perhaps the most ecologically important tree in Costa Rica's cloud forests. Its small, avocado-like fruits are the primary food source for the Resplendent Quetzal, one of the world's most beautiful and culturally significant birds. The tree's fruiting season directly influences quetzal breeding success and migration patterns.

Quick Reference

iNaturalist Observations

Community-powered species data

290+

Observations

186

Observers

📸 Photo Gallery

Photos sourced from iNaturalist community science database. View all observations →↗

Taxonomy and Classification

- Persea: Ancient Greek name for an Egyptian tree - caerulea: Latin for "blue" (referring to fruit color) - Aguacatillo: Spanish diminutive of "aguacate" (avocado) - Related to the cultivated avocado (Persea americana)

Common Names

Physical Description

Overall Form

The Aguacatillo is a medium to large evergreen tree with a dense, rounded crown. Its thick, leathery leaves have a characteristic bluish-green color, and the bark is grayish-brown with shallow fissures. The tree often develops a straight trunk with spreading branches that create important habitat structure in cloud forests.

Distinctive Features

Leaves

- Type: Simple, alternate

- Size: 8–15 cm long, 3–6 cm wide

- Shape: Elliptic to oblong

- Color: Glossy dark green above, bluish below

- Texture: Thick, leathery

- Fragrance: Aromatic when crushed

Bark

- Color: Grayish-brown

- Texture: Finely fissured

- Inner Bark: Reddish, aromatic

- Feature: Contains aromatic oils

Flowers

- Size: 4-6 mm diameter

- Color: Yellowish-green

- Arrangement: Small panicles

- Timing: January to March

- Pollination: Insects

Fruits

- Type: Drupe (mini avocado)

- Size: 1–2.5 cm diameter

- Color: Dark blue to purple when ripe

- Flesh: Thin, oily

- Season: March to June

Ecological Importance

The Quetzal Connection

The relationship between Aguacatillo trees and Resplendent Quetzals is one of the most important plant-animal interactions in Central American cloud forests. Quetzals are one of the few birds capable of swallowing the fruits whole and are crucial seed dispersers.

Why Quetzals Need This Tree

- Primary food source during breeding season

- High fat content (40%+) provides energy for nesting

- Fruit size perfectly matches quetzal gape

- Fruiting timing aligns with quetzal breeding

Seed Dispersal Services

- Quetzals regurgitate seeds intact

- Seeds dispersed far from parent tree

- High germination rates after gut passage

- Creates forest connectivity

Cloud Forest Ecosystem Role

The Aguacatillo is a keystone species in Costa Rican cloud forests:

- Food web anchor: Supports dozens of bird species

- Watershed protection: Deep roots stabilize steep slopes

- Carbon storage: Long-lived trees accumulate carbon

- Microhabitat creation: Epiphytes cover branches

Wildlife Associations

Beyond quetzals, Aguacatillo supports a rich web of cloud forest wildlife:

Ecological Adaptations

Cloud Forest Strategies

- Leathery leaves resist constant moisture and wind

- Aromatic oils deter herbivorous insects

- Dense crown captures fog drip, channeling moisture to roots

- Deep root system anchors tree on steep cloud forest slopes

Reproductive Strategy

- Abundant fruit production ensures dispersal even in low-density populations

- High-fat fruits attract reliable dispersers (quetzals)

- Sequential ripening extends food availability over several weeks

- Seeds require gut passage for optimal germination rates

Habitat & Growing Conditions

The Aguacatillo thrives in the misty conditions of tropical montane cloud forests. These forests are characterized by near-constant cloud cover, high humidity, and cool temperatures. The trees can tolerate occasional frost at higher elevations and are well adapted to waterlogged soils common on cloud forest ridges.

In Costa Rica, cloud forests occupy only about 1% of the national territory but harbor a disproportionate share of biodiversity. The Aguacatillo is one of the most common canopy trees in these ecosystems, often growing alongside oaks (Quercus costaricensis), magnolias, and tree ferns.

Distribution in Costa Rica

The Aguacatillo is found throughout Costa Rica's highland cloud forests, primarily between 1,200 and 3,000 meters elevation. Key locations include Monteverde, the Central Volcanic Range, and the Talamanca Mountains.

Key Observation Sites

Conservation Status

Current Status

While the species itself is not threatened, habitat loss and climate change pose significant risks to cloud forest ecosystems where Aguacatillo thrives.

Conservation Concerns

- Climate change: Cloud forests shifting upward in elevation

- Deforestation: Loss of forest connectivity

- Agricultural expansion: Pressure on forest edges

- Fragmentation: Isolated populations

Protection Efforts

Costa Rica protects significant Aguacatillo populations through:

- National parks (Los Quetzales, Chirripó, Braulio Carrillo)

- Private reserves (Monteverde, Savegre)

- Biological corridors connecting highlands

- Reforestation programs

Cultural Significance

Indigenous Heritage

The Aguacatillo holds deep cultural importance in Costa Rica's highland communities. The Cabécar and Bribri peoples of the Talamanca range have long recognized this tree as a guardian of the cloud forest. In traditional cosmology, the Aguacatillo is seen as a bridge between the terrestrial and spiritual worlds—its branches reaching into the perpetual mist that veils the mountains. The indigenous name "Yas" is still used in parts of the Central Valley and reflects pre-Columbian knowledge of the tree's ecological role.

Before European contact, indigenous communities used the Aguacatillo's aromatic bark and leaves in ceremonial preparations. The oils extracted from its fruits and leaves were valued for medicinal purposes, and the wood was used selectively for tools and construction elements that needed to resist moisture. This traditional ecological knowledge anticipated by centuries what modern science now confirms: the tree is a keystone species essential to cloud forest health.

The Quetzal and National Identity

The relationship between the Aguacatillo and the Resplendent Quetzal has become a powerful symbol of Costa Rica's conservation ethos. The quetzal—revered by the Maya and Aztec civilizations as a representation of the god Quetzalcoatl—depends on this humble tree for survival. Costa Rica's successful protection of quetzal habitat, including Aguacatillo forests, is celebrated as one of the country's greatest conservation achievements. The Savegre Valley, one of the world's best quetzal-watching destinations, owes much of its tourism economy to the Aguacatillo trees that draw these magnificent birds.

Ecotourism and Local Economy

Medicinal Applications

- Leaf infusions for digestive issues

- Bark tea for fever reduction

- Fruit oil for skin conditions

- Traditional cold and cough remedies

- Poultices for muscle pain

Ecotourism Value

- Primary draw for quetzal tourism

- Generates significant local income

- Supports conservation awareness

- Educational programs focus on tree

- Birdwatching guides identify fruiting trees for visitors

Wood Properties

While the Aguacatillo is primarily valued for its ecological role rather than its timber, the wood does have local uses:

The wood is soft to moderately hard, with a fine, even texture. It is not commercially traded as timber but is used locally in highland communities for:

- Rural construction: Fence posts, house beams (where naturally available)

- Firewood: Burns slowly with pleasant aromatic smoke

- Crafts: Carved utensils and small tools

- Essential oils: Bark and wood distilled for aromatic compounds

Harvesting Aguacatillo for timber is not recommended and is restricted in many protected areas. The tree's ecological value as quetzal habitat far exceeds any timber value. Sustainable alternatives should always be preferred.

Growing Aguacatillo

Cultivation Requirements

Propagation Guide

Reforestation Potential

The Aguacatillo is increasingly used in cloud forest restoration projects:

- Essential for quetzal habitat recovery

- Relatively fast growth for highland species

- Provides early food source for wildlife

- Helps restore forest canopy structure

- Acts as a nurse tree for slower-growing species

- Supports epiphyte communities within 5–10 years of planting

If your property is above 1,200 m elevation with reliable rainfall, planting Aguacatillo is one of the best ways to attract quetzals and other cloud forest wildlife. Several Costa Rican nurseries near Monteverde and San Gerardo de Dota sell seedlings. Contact local conservation organizations like CATIE or FUNDECOR for guidance on cloud forest restoration.

Identification Guide

How to Identify Aguacatillo in the Field

Quick Identification Checklist:

Key Differences from Similar Species

Similar Species

Interesting Facts

Where to See Aguacatillo

Where to Find Aguacatillo in Costa Rica

Best Quetzal-Viewing Locations (with Aguacatillo):

When to Visit:

Local guides know which Aguacatillo trees are currently fruiting and where quetzals are actively feeding. Hiring a guide dramatically increases your chances of seeing quetzals visiting these trees—a truly magical experience.

External Resources

Community observations and photos

Global distribution data

Botanical nomenclature

Kew Gardens taxonomic information

References

📚 Scientific References & Further Reading

Wheelwright, N.T. (1983). Fruits and the ecology of Resplendent Quetzals. The Auk

Zamora, N. et al. (2004). Árboles de Costa Rica Vol. III. INBio, Santo Domingo de Heredia

Kohlmann, B. et al. (2010). Cloud forest flora and fauna. Costa Rica: Natural History

Nadkarni, N.M. & Wheelwright, N.T. (2000). Monteverde: Ecology and Conservation of a Tropical Cloud Forest. Oxford University Press

The Aguacatillo (Persea caerulea) stands as a silent pillar of cloud forest ecology—a tree whose existence is inextricably linked to the Resplendent Quetzal and the health of Costa Rica's highland ecosystems. Every fruit it produces sustains the birds that captivate visitors from around the world, and every seed those birds disperse plants the next generation of forest. To protect the quetzal, we must protect the Aguacatillo.

Safety Information Disclaimer

Safety information is provided for educational purposes only. Individual reactions may vary significantly based on age, health status, amount of exposure, and individual sensitivity. Always supervise children around plants. Consult a medical professional or certified arborist for specific concerns. The Costa Rica Tree Atlas is not liable for injuries or damages resulting from interaction with trees described in this guide.

• Always supervise children around plants

• Consult medical professional if unsure

• Seek immediate medical attention if poisoning occurs

Information compiled from authoritative toxicology sources, scientific literature, and medical case reports.